If Florida continues growing at its current pace, more than 2 million acres of the state’s ranches, timberland and farms could be paved over to make way for another 12 million new residents by 2070, according to a new report from the University of Florida and 1000 Friends of Florida.

That would mean the loss of crucial wetlands, prairies and forests that fight flooding, rising temperatures and other threats from climate change and the destruction of crucial habitat for panthers, bonneted bats and other disappearing animals.

READ MORE: Shutting an agency managing sprawl might have put more people in Hurricane Ian’s way

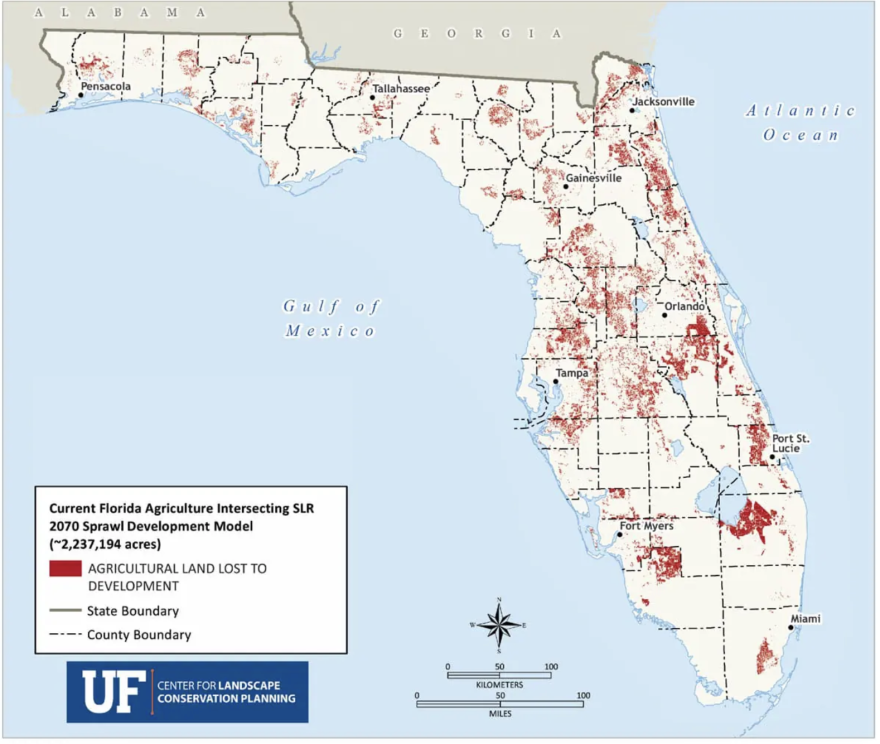

The report is the second in a project that also looked at land loss to sea rise and sprawl, which could wipe about a million acres. Combined, total loss would add up to about 3.5 million acres of undeveloped land lost over the next 50 years, or about 150 cities the size of Miami or Fort Lauderdale.

“I would hope most people would consider that not to be sustainable,” said Tom Hoctor, director of UF’s Center for Landscape Conservation Planning. “Once you lose it, you’ve lost it. For good.”

Of Florida’s nearly 36 million acres, about a third remains in ag use, from timberland growing amid ancient forests from the Panhandle and the Big Bend to ranches stretching from Orlando to southwest Florida.

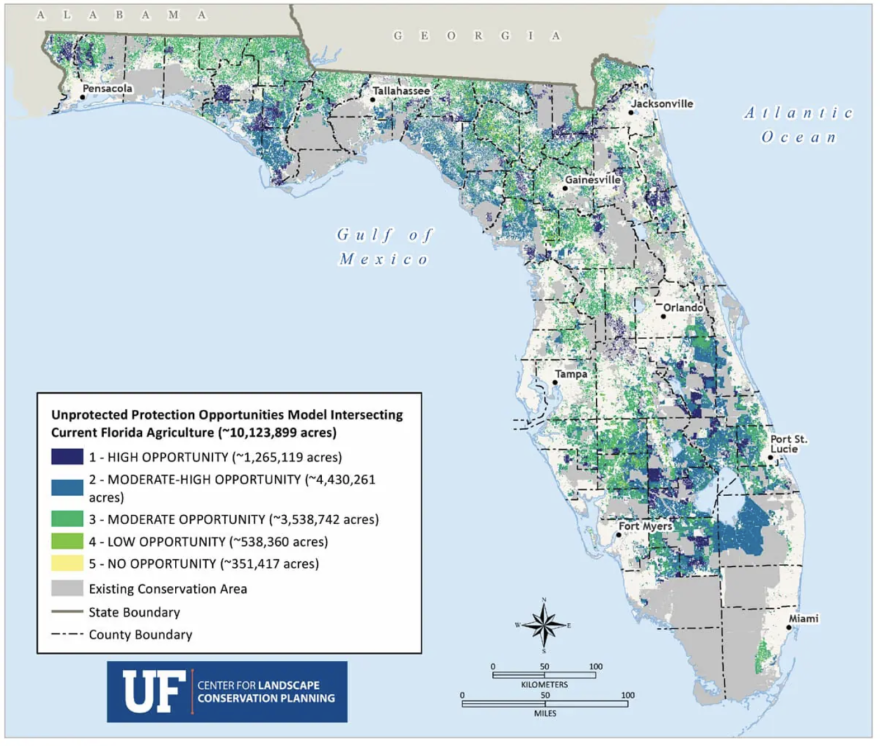

Ranches make up the biggest portion, with about a half million acres of pastures providing habitat for panthers. While some ag land has been protected over the years with easements that prevent development, the report found a far greater amount — more than 80 percent — remains unprotected.

In just 50 years, swaths of ag land southeast of Lake Okeechobee, in western Miami-Dade County and northeastern Collier County, among other places, could become neighborhoods, the report found.

That flood of new people — between 800 and 1,000 over the last few decades — is driving up land prices as ag operations become less profitable, said Jim Strickland, whose family has been ranching in southwest Florida for six generations.

“We used to have 3 million cows at one time with a million people. We now have 18 million people with 1 million cows,” he said. “This is not doom and gloom, but a lot of agriculture is on life support.”

And Florida conservation programs date back to the 1960s that have not kept up.

The Florida Wildlife Corridor, approved by the state in 2021, builds on former conservation programs, including Preservation 2000 created in 1990. But so far, only about half the land needed to complete the corridor has been protected. A follow-up conservation program, Florida Forever, was created in 2000, but fizzled over the years, going largely unfunded until three years ago.

As land prices soared, state money for conservation easements did not, Strickland said.

“Nobody’s breaking our arms to sell [but] the opportunities financially are hot to sell,” he said. “It’s a very tough decision and I’ve sat around the table with a lot of different families, a lot of different landowners, and it is a hard decision …to do a conservation easement for different reasons.”

Last year, Gov. Ron DeSantis vetoed $100 million lawmakers set aside to buy development easements on ag lands. And money approved by voters for conservation in 2016 to establish the Land Acquisition Trust Fund that would amount to about $20 billion over 20 years, has largely gone to Everglades restoration. That means it can take years for easements to be purchased once landowners apply.

“Those years that we’ve had $15, $17, $20 million, it doesn’t go very far,” Strickland said. “And if you stand in line long enough, eventually your feet get sore and you’re going to look for other opportunities to sell that land.”

The state also did away with the agency that oversaw growth management more than a decade ago and has repeatedly weakened growth management laws, making it easier for developers to push boundaries meant to protect sensitive land.

In Miami-Dade County, developers won approval to build a warehouse fulfillment center on an old Everglades slough last year. And so far, just over half the land needed to create the Florida Wildlife Corridor, a trail for wildlife stretching from the Keys to the Panhandle, has been protected.

“I’ve been encouraged in the last few legislative sessions to see what I would call a pendulum swing towards recognizing the importance of land conservation. But a couple years isn’t good enough,” UF’s Hoctor said. “They’re thinking about election cycles and things that are going on now. If you’re going to do sustainability planning, you have to be willing to think long term into the future.”